by Aaron Tay, Lead, Data Services

In a recent survey of SMU faculty, Google Scholar came up tops as the most popular starting point used by faculty to explore scholarly literature.

This is not a surprise given that Google Scholar is the largest source of academic content, its ability to index and match full-text of most papers, coupled with the power of Google’s relevancy algorithms all wrapped up in a user-friendly interface means that it is unmatched as a general academic search engine, particularly if you do not mind an inclusive search that includes results from sources that may not be from top tier journals or might even be considered possibly predatory journals.

What you may not realise is these strengths also mean that Google Scholar serves as an excellent tool to help you keep track of research that you might be interested in.

Here are the 3 different ways.

Google Scholar allows you to set up saved alerts by email

Like any academic search engine or database, Google Scholar allows you to set up alerts based on past keyword searches.

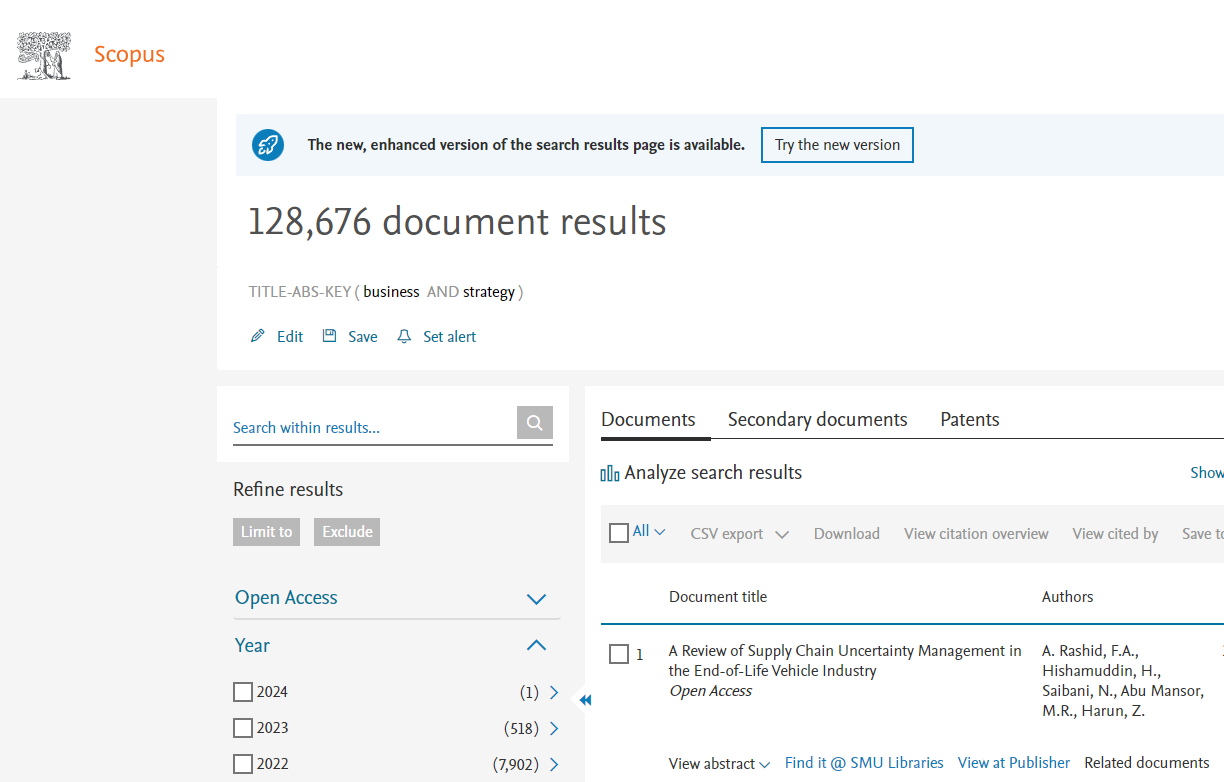

So why use Google Scholar over a traditional cross-disciplinary database like Scopus or Web of Science or even publisher platforms like Elsevier’s Sciencedirect, Wiley Online Library (Wiley), Sage Journals (Sage) etc for searching or alerts?

Firstly, research has shown that Google Scholar indexes new papers from publisher sites far faster than traditional citation indexes like Scopus or Web of Science. This presumably results in faster alerts than using Scopus or Web of Science and is only days behind publisher platforms.

Publisher platforms from Wiley, Sage, Elsevier are excellent for tracking individual specific journals but the literature in most disciplines are spread across multiple publishers, so you should not rely only on one Publisher platform for your literature review or research alerts.

Secondly and more importantly traditional citation indexes like Scopus or Web of Science or Publisher Platforms do not include preprints from preprint services like arxiv, SSRN in their main search index. If finding or keeping tabs of relevant research in very early stage is important, Google Scholar is a better bet since they can surface such papers in searches or via email alerts.

Of course, the fastest way to keep track of research is to go directly to preprint servers used by your research community and search or browse. Depending on the preprint server in question, you may be able to create a saved alerts.

For example, SSRN does not allow saved keyword alerts, the alerts offered are by ejournal level via different Research networks site subscriptions (e.g. Accounting Research Network, Financial Economics Research Networks. Consult your research librarian for more details.

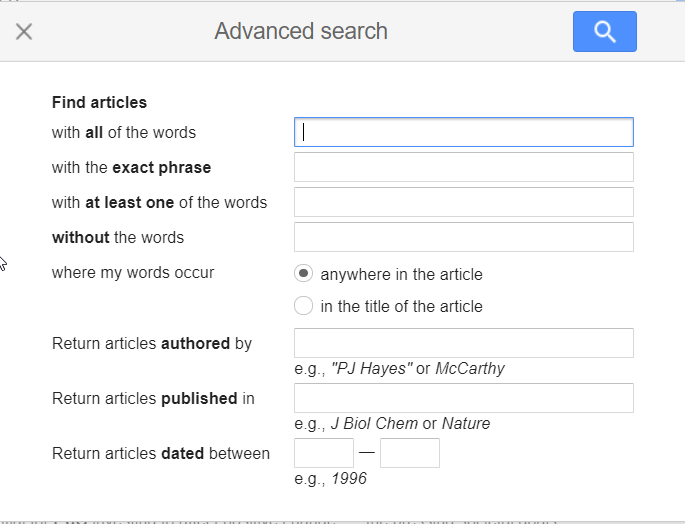

How to setup alerts in Google Scholar

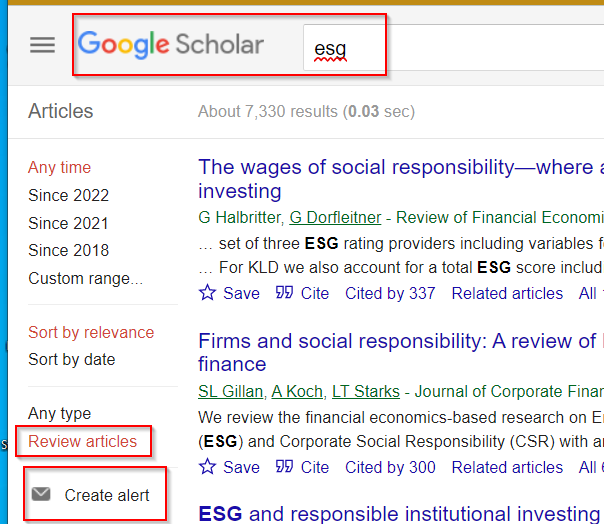

Like most such systems, you will need to do a keyword search before setting up the saved search. You can use the standard basic search in Google Scholar or use the Google advanced search interface.

Once you are happy with the results, you can click on “Create alert” on the left pane to create a alert (you will need to be logged in to your Google account).

In the example above, I searched Google Scholar with the simple keyword ESG and then filtered the results to “Review articles”. I want Google Scholar to email me whenever new articles are found that match this search, so I click on “create alert”

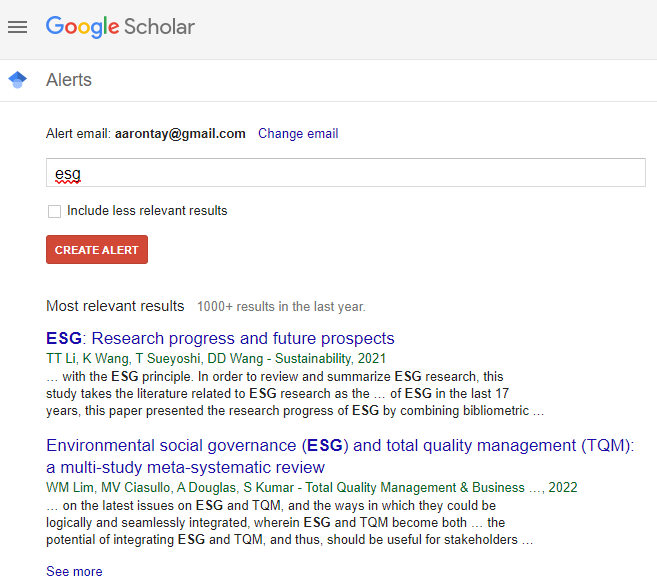

On the next screen, it shows the email the alert will be sent and some typical results.

It is often difficult to estimate whether the search you have done is too broad or narrow and Google Scholar tries to help you by showing you that for what it considers the “most relevant research” you get about 1,000 hits based on history of the past year.

You can also see a sample of results of what it considers “most relevant research”. If you scroll down further, it shows that for what it considers for “less relevant research” you would also get about 1,000 hits as well as highlighting some results from that set.

Given this information you can

- Just Create the alert

- Check on “include less relevant results” and create the alert

- Start all over again with another keyword search

Based on the results this seems to be quite a broad search and I personally would choose option a) or c) but that is your choice.

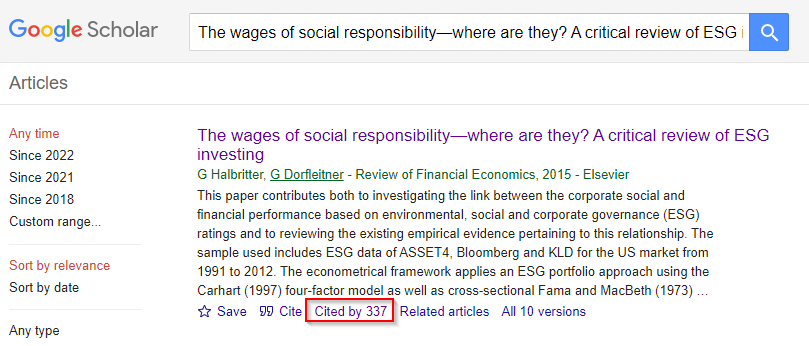

One more interesting trick you can do is to create alerts based on citations made to important papers.

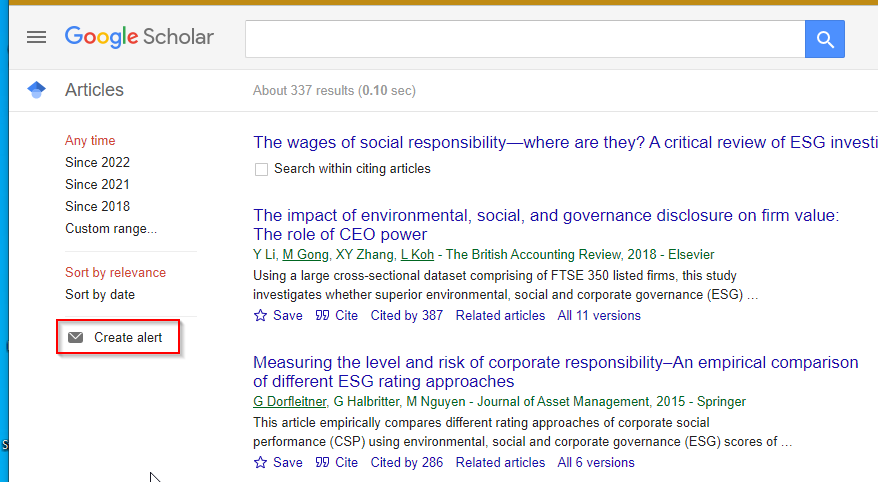

Say for example you identify that “The wages of social responsibility—where are they? A critical review of ESG investing” is an important paper and you want to be alerted whenever this paper gets a new citation. You can simply click on cited by link and then create an alert on the paper on the resulting page.

In fact, you can do even more granular searches.

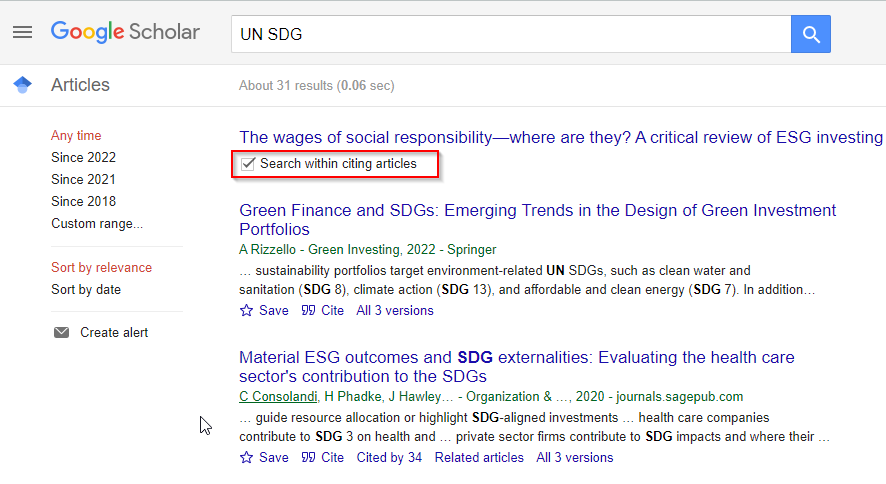

Imagine if you wanted not to be alerted of every citation to the paper “The wages of social responsibility—where are they? A critical review of ESG investing”, but only be alerted if the citation includes the keyword “UN SDG” in full text of the citing papers.

No problem, first type in UN SDG, check “search within citing papers” and search.

On the resulting paper click “Create alert” as before.

Google Scholar automatically recommends papers of interest based on your Google Scholar profile and alert

Setting up alerts based on keywords is well and good. But it is sometimes difficult to define the right keywords to get what you want. Setting up alerts based on citation alerts (see above) is one way to help.

But the latest recommender systems-based now work by telling the system , “I want more papers like this one”. The system will then use various (often non-transparent) criteria such as citation similarity or text similarity or co-use etc to recommend similar papers without the need to set up explicit search rules.

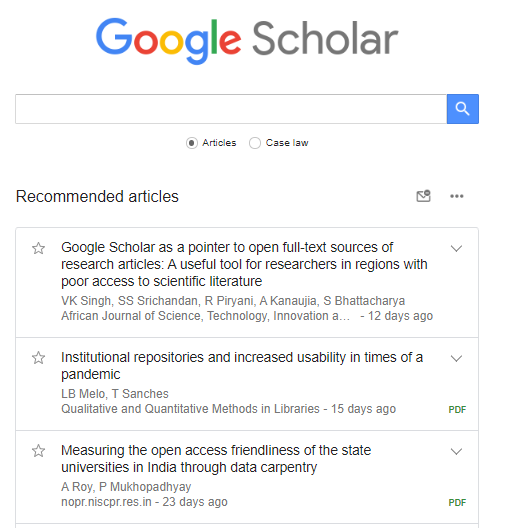

Google Scholar’s version of this feature is called “Recommended articles”.

You will get alerts of these recommended articles via email, but they will also always be displayed on the home page of Google Scholar (assuming you are signed on).

But how does Google Scholar know what to recommend? Google Scholar states that “ “These recommendations are based on your Scholar profile and alerts.”

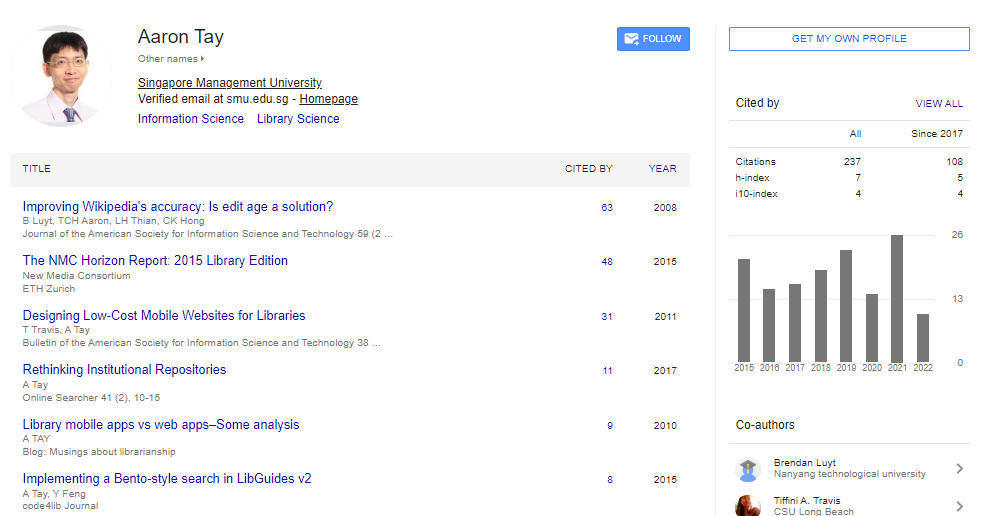

If you are unfamiliar with the Google Scholar profile it is basically a profile where you list papers you have written.

Above shows my personal profile and Google Scholar uses those articles as a base to recommend items. As noted in the documents, Google Scholar also uses your saved queries to recommend additional items that may not match the keywords.

Alternative: In my personal experience, the recommendations from this feature are often the most on target and most timely as compared to the manual saved email alerts.

However, if you are a student or a researcher seeking to move into a new area, your Google Scholar profile will not have any relevant items for Google Scholar to use to recommend suitable items. If you prefer this style of recommendations, you may consider using alternative academic search engines like Semantic Scholar or tools like ResearchRabbit that can make recommendations on specific items you have selected.

Google Scholar lets you follow author profiles and related works

So far, we have seen multiple ways where Google Scholar allows you to be informed of potentially relevant articles by looking at characteristics of articles.

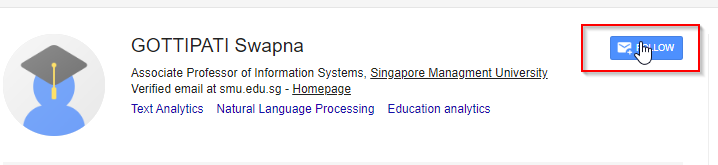

An alternative to this is to take an author centric view. As mentioned earlier, Google Scholar hosts profiles for authors. You can search for profiles directly here, or as you search through Google Scholar, click on highlighted author names under each Google Scholar result.

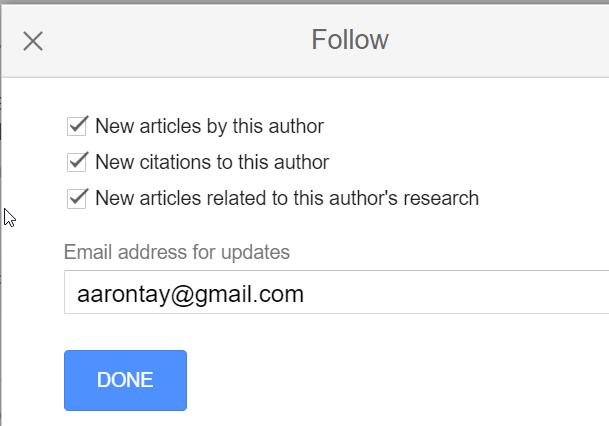

Say you land on an author profile page in Google Scholar, and you are very interested in things relating to their works. Google Scholar offers three options here.

As noted in the screenshot above, you can get recommendations when

- New articles are added by the author

- New citations are made to papers by the authors

- New articles related to the authors' papers are added (It is unclear how “related” is determined).

While this is a very useful feature if you can find an author with interests very similar to yours, in my experience the recommendations from this option have the potential to result in many irrelevant alerts.

This is because it is very common for authors to publish in multiple areas, some of which may not be of interest resulting in recommendations that are useless to you.

Conclusion or why not Google Scholar

Google Scholar is indeed a powerful tool not just for searching but also for setting up what librarian’s call “current awareness” services. That said, Google Scholar does have several well documented weaknesses including

- Overly broad scope that might result in extreme number of results and/or low-quality results.

As is well known, Google Scholar covers any content that looks academic and this is determined almost wholly by algorithms. This means it will include many works that are not proper academic content (e.g., library guides) or worse predatory journal content.

- Coverage of papers by certain journals might be incomplete.

- Do a saved alert using more curated citation indexes like Web of Science or Scopus

- Use BrowZine (via SMU Libraries) to get alerts of new issues

- Get table of contents for target journals using individual RSS feeds or via services like JournalTOCs

Google Scholar relies on crawlers to crawler publisher websites to include journals, while this enables it to index new papers far faster than traditional citation indexes like Scopus which have some amount of human curation, the fact that it is automated also means crawlers may miss certain papers or more commonly result in metadata errors.

If speed of updates isn’t of an essence, and the cost of missing out new papers from specific journals is high you can consider the following options instead for specific individual favorite journals

- Google Scholar does not cover all academic content types

While Google Scholar covers a wide variety of academic content types, including journal articles, conference proceedings and even preprints from preprint servers as well as various grey literature items, it may not surface monographs or datasets. It also generally does not cover thesis or dissertations.

While searching in Google Scholar might occasionally show you some book results from Google Books, this isn’t guaranteed and if your interest is in academic books, you are probably better off using Google Books directly.

At the end of the day, as useful as Google Scholar is, it is just one system and you may need to combine it with other systems such as a subject specific database for a more complete picture.