By Heng Su Li, Co-founder of SMU Researcher Club, Research Associate (Cooling Singapore 2.0, WP-B)

On 25 June 2024, the SMU Researcher Club rolled out the fourth session of its Publication Series, titled My Paper is Rejected. What Now?. It featured perspectives from experienced SMU researchers of different research disciplines and backgrounds on a moderated panel. They are Dr. Andree Hartanto (Associate Professor of Psychology (Education), SOSS), Dr. Hari Chittor (Research Scientist, SCIS), Dr. Panchali Guha (Research Fellow, SOSS), and Dr. Jude Kurniawan (Postdoctoral Fellow, Sustainability and Governance, SOSS; Moderator).

The session explored the issue of paper rejection, focusing on the impacts on researchers and strategies to move forward while preserving and optimising their work. The panelists shared their experiences with such rejections, as well as how they overcame and turned the rejection into a stepping stone for future success. This session also featured a sharing on Open Access Publishing and Transformative Agreements by Yeo Pin Pin (Head, Research Services, SMU Libraries). If you're interested in the session’s takeaways, keep reading!

Understanding the Editorial Process(es) leading to an Acceptance, Revision, or Rejection

In the first session of the Publication Series, Pin Pin shared that a Journal Impact Factor (JIF) is a useful indicator for researchers to assess the journal they want to submit their papers. The comic below, where the JIF formula has been adapted to measure a researcher’s impact factor, points to the issue that a researcher’s worth (not accounting for their employers’ measurements) is largely measured by their publication numbers and citation count. As such, researchers need to strategically approach publishing to maximise their chances of acceptance.

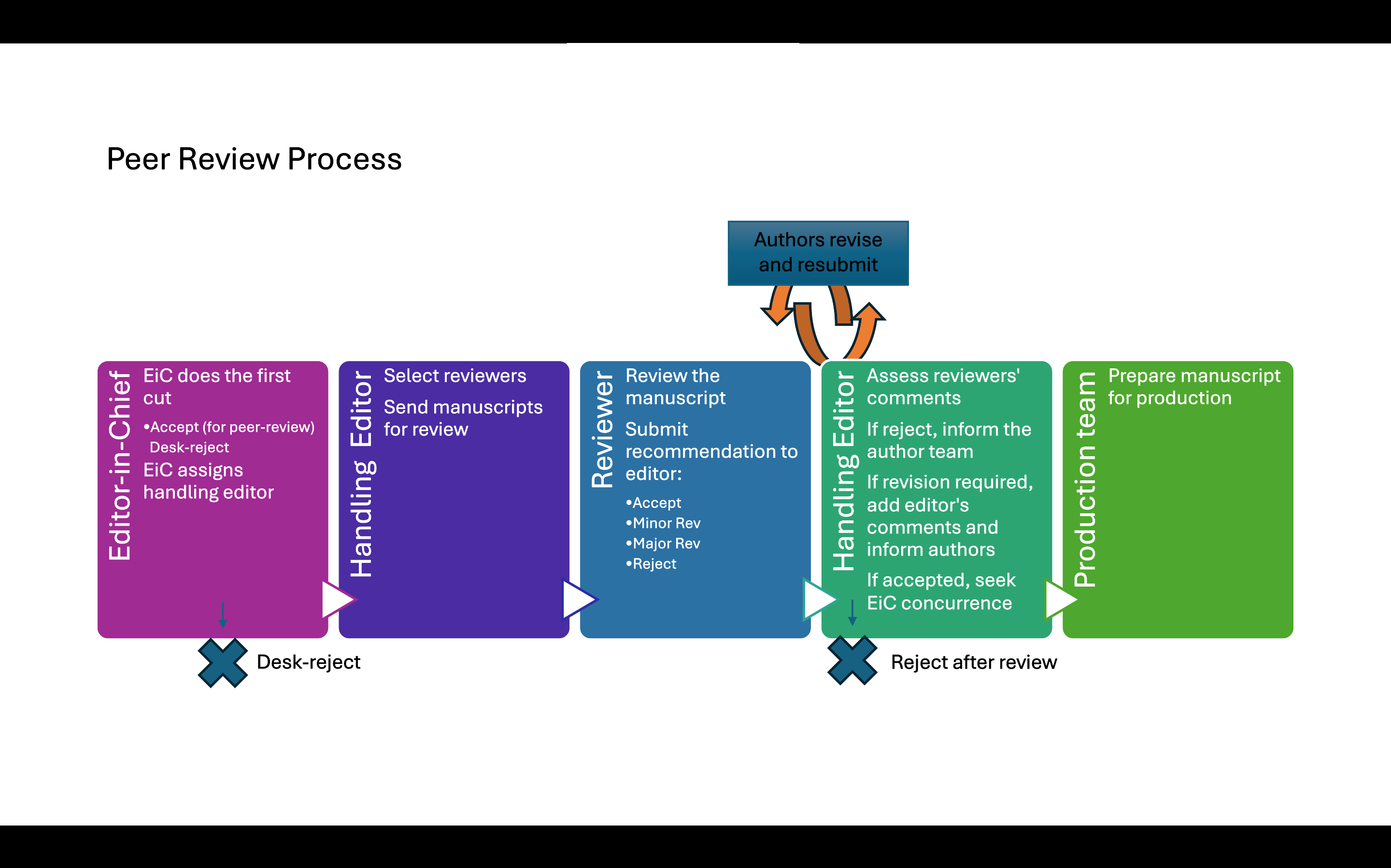

To do so, researchers should understand how editorial and peer review processes, both determining the fate of your submission, work. As Assistant Managing Editor & Editorial member for the International Journal for Smart and Sustainable Cities, Jude summarised the processes and stages in the flow chart below (Figure 1).

Desk rejects

Desk rejects are issued by the editor-in-chief (EIF) and can happen for various reasons. A poor fit between your manuscript and the journal’s scope is one of the biggest reasons your manuscript is rejected right from the get-go. Sometimes, EIF doesn’t see the novel contributions of your work. Especially for special issues, your work may be rejected because there are just too many submissions.

Panchali and Andree both agreed that abstracts are an important first-cut criterion, as they allow the work to stand out from the huge volume of submissions. As such, ensuring that your abstract and title are enticing and compelling may help with clearing desk rejection. Hari’s approach is to read papers outside of his domain; if he understands the abstracts and can see how they fit the paper, he learns from the abstracts and it helps him in writing more compelling abstracts.

Knowing who the EIC is, and his/her background will also help researchers in their strategies. Andree and Hari highlighted the need for researchers to understand which camp the EIC sits in that discipline (usually there are different ‘camps’ and some may be at odds). Andree also observed that at his level, the EIC’s preference for the manuscript largely determines whether it will be accepted or rejected. However, knowing the EIC (personally or not) will likely help with passing the desk reject but no more. This is because the handling editor may not know you and is the one assigning the reviewers.

Who are (peer) reviewers?

When manuscripts are submitted, the handling editor looks out for experts in similar fields to review the manuscripts. Reviewers are usually someone well-regarded as experts in the field. They are selected for various reasons, including but not limited to – (1) their publication histories; (2) their works are cited heavily in the submission; (3) they have a good track record in their past reviews and review assignments in progress; and (4) their profiles’ keywords match the submission’s keywords.

As researchers in a similar field would likely know each other, there can be conflicts of interest (COI). Authors are expected to disclose the COI when putting forward names of potential reviewers. The handling editor may or may not select these potential reviewers.

In some cases, the review process is partially blind; authors will not know which reviewers are picked, but reviewers (from my experience) will know who the authors are after accepting the request to review and seeing the manuscript. There are other peer review models where less information is available (e.g. double blind) but even in such cases, if the topic is a niche one, it may be easy for the reviewer to guess who the author of the work is and vice versa.

On a tangential note, there are multiple upsides for a researcher to review manuscripts. First, the reviewer scores ‘points’ in terms of service to the community. Second, reviewing manuscripts enables the reviewer to get up to speed with the state-of-the-art methods, literature, and gaps in similar fields. Third, the reviewer and author are simply different sides of the same coin. Learning to be a good reviewer will make you a better writer. The standards a reviewer uses to pick the manuscript apart (e.g., are there too many research questions (RQ), does the conclusion match the original RQ, spelling/grammatical errors, etc.) will be the same ones an author uses when vetting his/her manuscripts before submission. You may refer to the resources segment to see the resources Jude shared.

Also, researchers do not have to have a PhD or an academic appointment to be selected as a reviewer. If you are pursuing your postgraduate degree and have been approached to review a submitted manuscript, the panelists strongly encourage you to do so, with the following considerations. First, you should ensure that you are credited for your review work. If you are doing the service because your professor assigned it to you, you can suggest that the professor add your name to the editorial manager system so that the review request can be formally directed to you. Second, reviewing will take a lot of time when you first start (you will become more familiar and efficient the more you review), so it is important to ensure that your main deliverables are met.

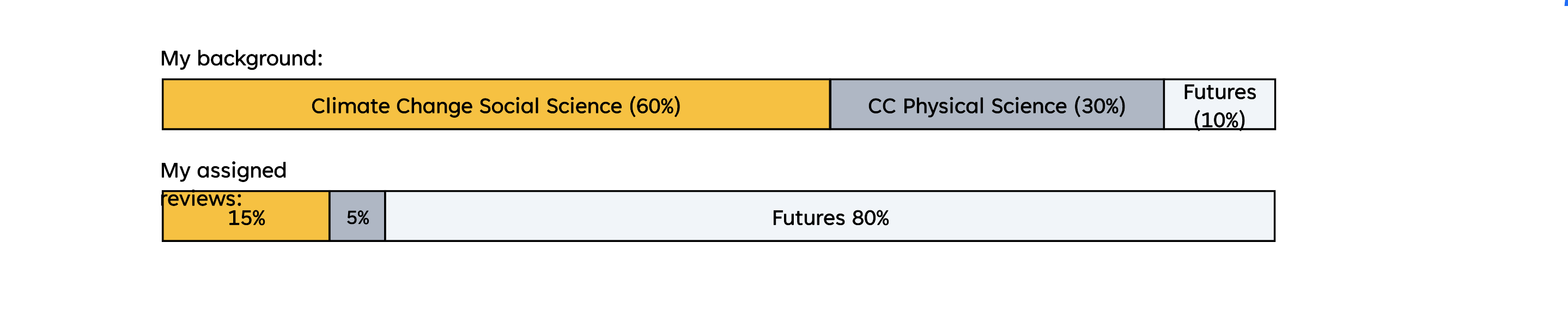

An interesting point Jude highlighted is that the review requests you receive shed light on how your colleagues (i.e., authors and handling editors in similar fields) perceive your work. He conducted an internal review of his work (i.e., publications) and the assigned reviews (i.e., submissions assigned to him) and found that Futures-related work, which forms ~10% of his total work, draws the biggest proportion of the manuscripts (~80%) that he has been asked to review (see Figure 2). This exercise could be conducted as part of a researcher’s regular stocktake of their work.

Understanding revisions and rejections

At this stage, we assume that the manuscript has passed the desk reject, and the comments from the reviewers don’t look too optimistic. Our panelists shared the types of common mistakes/inherent issues that can lead to such situations. Panchali pointed out that there are easier- and harder-to-fix issues. Scope mismatch and methodological preferences by the journal, as well as writing errors, are relatively easy to fix; you can send your manuscript to a more appropriate journal or clean up the writing errors and resubmit to the same journal. Harder-to-fix issues include design issues with research methods (e.g., the sample size is too small) and outdated methodology (e.g., not the latest development), with the latter resulting in a lack of novelty. For the harder-to-fix issues, researchers may have to choose another journal down the prestige ladder.

Although taking a step back, researchers need to understand the journal (and the chances of acceptance) they intend to submit to. Hari shared that in his discipline, researchers need to identify the journal and scan a few of the papers in there to learn from the formatting and prepare directly in that format. In short, choose the journal first then write, and not the reverse.

Panchali implements a structure that allows her to respond quickly after a rejection. Before submitting to any journal, she does a spreadsheet with 5-10 relevant journals. This spreadsheet contains relevant information like JIF, the journal scope, and a short list of recently published papers in the journal with similar topics to your manuscript. This allows her to quickly re-edit her manuscript to fit the new journal’s format.

Hari and Andree highlighted the importance of going through the reviewers’ comments. Hari recommends researchers address reviewers’ general comments, even if they plan to submit to other journals. This is because researchers may get the same reviewers in different journals. As Andree pointed out, Business Schools tend to focus on prestige journals, leading to very few journals to submit to and naturally a very small pool of reviewers.

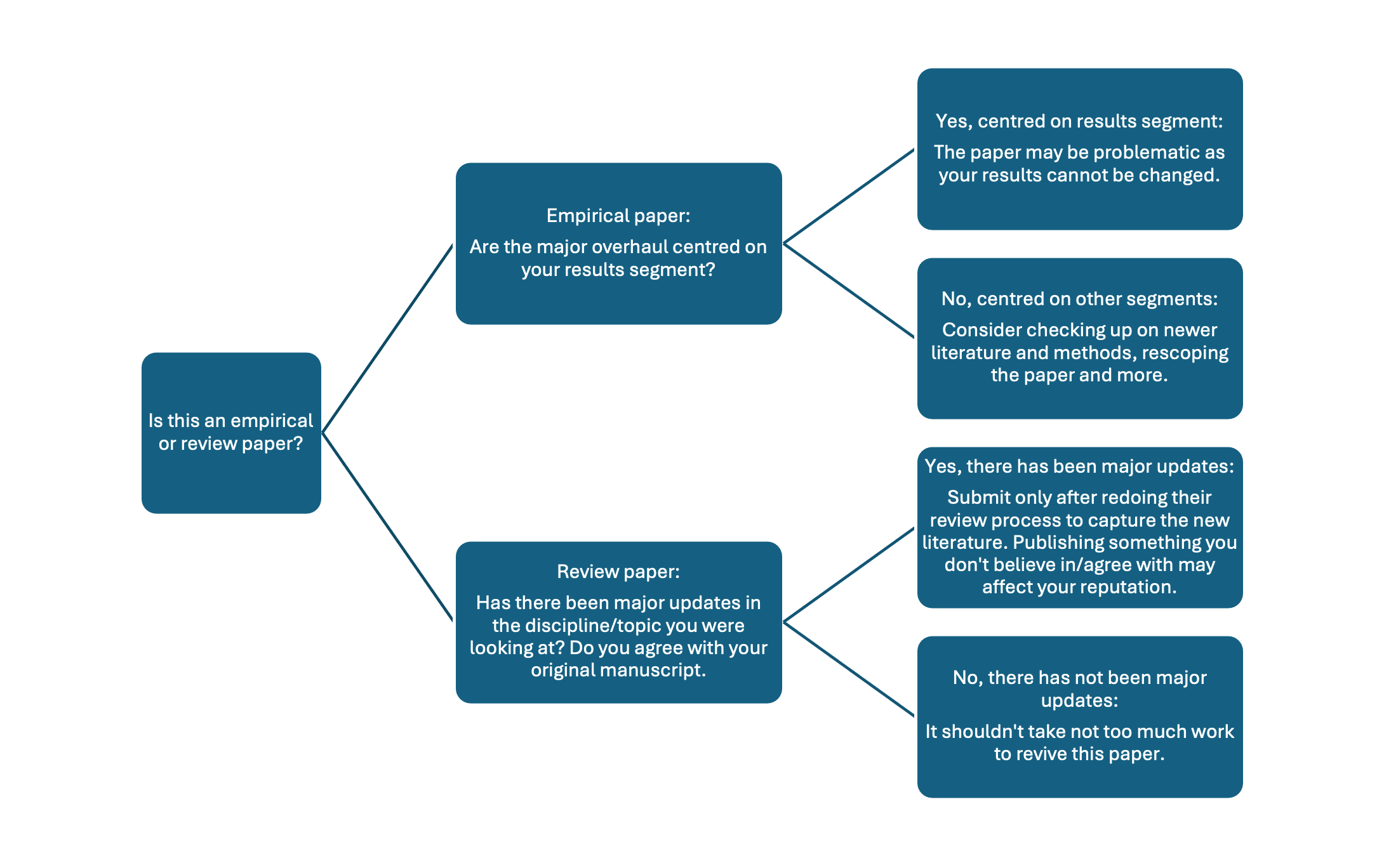

Some of our researchers may also be faced with the situation of trying to revive a rejected paper that has been untouched for an extended period. Should the work die, or be revived even if it requires a lot of effort? Our panelists have some guidelines, which I’ve summarised in the decision tree below.

Rejected for reasons outside of your control

Sometimes, manuscripts can be rejected for reasons beyond the authors’ control. Some researchers observed or hypothesised that their backgrounds – a non-English-looking name, from a smaller institution, etc – may affect the rejections, on the assumption that their writing is subpar or that they lack credibility.

Our panelists cannot say for certainty that their rejections are tied to their names (all our panelists do not have English-looking (sur)names). Nonetheless, they’ve adopted various strategies to build their credibility. For example, authors can cite their work to show that they have established peer-reviewed papers. To put this into practice, I (my surname is Heng) can cite one of my past works in the manuscript, preferably one that comes out explicitly as “Heng and Someone (YYYY)” or “Heng et al., (YYYY)”. This approach is possible only if I have first-author paper(s). If you are in your early career, it helps a lot to work with an established researcher as a co-author for the manuscript.

Responding to reviewers’ comments

Andree pointed out that revise-and-submit is one of the toughest parts of research, as it is common to disagree with the reviewers’ comments. Earlier in his career, he incorporated and addressed the reviewers’ comments but could not recognise some of his work as they had become “like a Frankenstein”. Now, he is firmer in deciding which comments to address or not. As a supervisor, the strategy for his students is to be polite with the reviewers, because the students need the papers published.

Having a template to guide how the author responds to the reviewers can make the process less painful. Authors can list the reviewers’ comments in a column and write a corresponding response or recommendation to each comment. Hari and Panchali have similar approaches. Hari thinks it is good practice to show the original and edited versions of the manuscript explicitly (e.g., stating specific lines, segments, and paragraphs) to show how the reviewers’ comments have been addressed. The edits can be shown in different visuals in terms of font type, font colors, and highlights. Panchali’s method also echoes the importance of showing the before and after, using this structure:

My original statement was “X”, and the new statement is “Y”, thereby addressing your ABC comments.

A notable tip that the panelists shared is to respond respectfully. Researchers who are frustrated and upset at the reviewers’ comments can consider using ChatGPT to churn out the preliminary response. This helps to remove the researchers emotionally from the reviewers’ comments. Hari pointed out that it is not uncommon for reviewers to make a mistake in their comments. Authors can respond that the comments are addressed in the original manuscript and show where exactly in the original manuscript. It is not about telling reviewers that they made a mistake. Our panelists also advise against ignoring comments you do not agree with. It is important to acknowledge the perspective of the reviewers, and then explain why you disagree. Researchers can do so by giving 3 key reasons, each substantiated.

Interestingly, Andree recalls instances where his responses are longer than his manuscripts. He hypothesises that the higher the reviewers perceive his effort, the higher the chances of the manuscript being accepted.

Researchers may consider asking for an extension in responding to the reviewers, although it can be a double-edged sword. The upside is that if there are any emotionally charged decisions or comments from the reviewers then, the extension distances the reviewers from the manuscript. The downside is that if the reviewers go out of touch, a new reviewer will be appointed, forcing the authors to undergo the process again. A long extension can also be detrimental if ideas in the disciplines become outdated quickly, especially in computer science.

Coping with rejections and trauma

Our panelists agree that feeling down after their manuscripts have been rejected is normal and that rejections are common in academia. Hari rightfully made the distinction between rejection and failure. Rejection is not equal to failure. (Did I repeat the point? Yes, because it is important). Rejection should be taken as part of a learning process. Researchers will eventually become better at overcoming rejections and perhaps position themselves to receive less rejections.

Rejection can happen to anyone. For Andree, researchers must accept that rejection is normal; it can happen during PhD applications, in ‘rejections’ from supervisors, funding agencies, or journals. Panchali pointed to the “CV of failures” by Johannes Haushofer, who bravely posted the list of programs he did not get into and academic positions he did not get. (Sidetrack, as I was writing this recap, I realised that a CV of failures could be better packaged as a CV of rejections). Nonetheless, a stocktake of such ‘rejections’ makes a paper rejection less painful.

What matters is processing the emotions and bouncing back. Researchers who have been traumatised may consider setting up a system to track all the editors and/or reviewers whom you have blacklisted for making the process difficult, as a coping mechanism. Confiding in your supervisor is also another way. For some researchers, one way to overcome the rejection is to submit more papers, so the rejection(s) “feel(s) less painful”.

Publishing wherever and whatever

Jude raised a controversial question – Should you publish in a predatory journal or any open-access (OA) platforms to get your work out there? It can be tempting to do so after many rejections. The short answer is no.

The nuanced answer is to understand that predatory journals tend to exploit the OA publishing model to make money from author fees by accepting most or all papers submitted to them. It is almost impossible to be rejected. Andree hypothesises that most journals will become OA to some extent soon, so there is little value in publishing in a predatory journal, which will be highly damaging to a researcher’s career.

Hari and Panchali recommended the go-down-the-prestige-list approach. There are less prestigious OA journals (e.g., Frontiers, MDPI, etc.) that are still good alternatives due to their wide readership and citation. For Hari, it is fine to incorporate the comments and perhaps aim for journals up the prestige ladder. His work, rejected at a mid-tier conference, was accepted in a higher-tier conference after he incorporated the comments.

Researchers whose work is constantly rejected due to a ‘lack of novelty’, or lack of significant results may grow to self-censor their work. In other words, they deliberately do not put their work into a manuscript for submission in fear of rejection. Andree highlighted that his lab’s culture is to publish regardless of results, given the replication crisis (See this piece for a readable coverage of the replication crisis). As such, OA journals are a good venue for these papers as they are likely to be rejected by the more prestigious journals.

SMU Libraries on Open Access Publishing

Pin Pin gave a quick sharing on OA publishing and transformative agreements, which cover the cost of Article Processing Charge (APC) for SMU Researchers. SMU Libraries has established two deals currently with the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM Open) and Cambridge University Press (CUP). Do note that these apply only when the corresponding author is a SMU researcher, i.e. affiliated to SMU having a valid SMU email address.

After the manuscript is accepted, SMU researchers are given the option to make their papers open and freely accessible. The corresponding author needs to undergo a process to activate the benefits of transformative publishing. For more details, please refer to our earlier ResearchRadar articles on transformative deals with ACM and CUP. If you have papers published after Jan 2023 and would like to take advantage of these deals, please reach out to SMU Libraries.

Resources

Jude recommends the following resources:

- The Elements of Style by William Strunk Jr. (Author), E. B. White (Author): For writing concisely.

- Writing classes: Writeonline.ca

- Writing tools: Grammarly; Referencing software: Zotero, Mendeley; and Local LLM (LM Studio)

- Things to take note of as a reviewer and author:

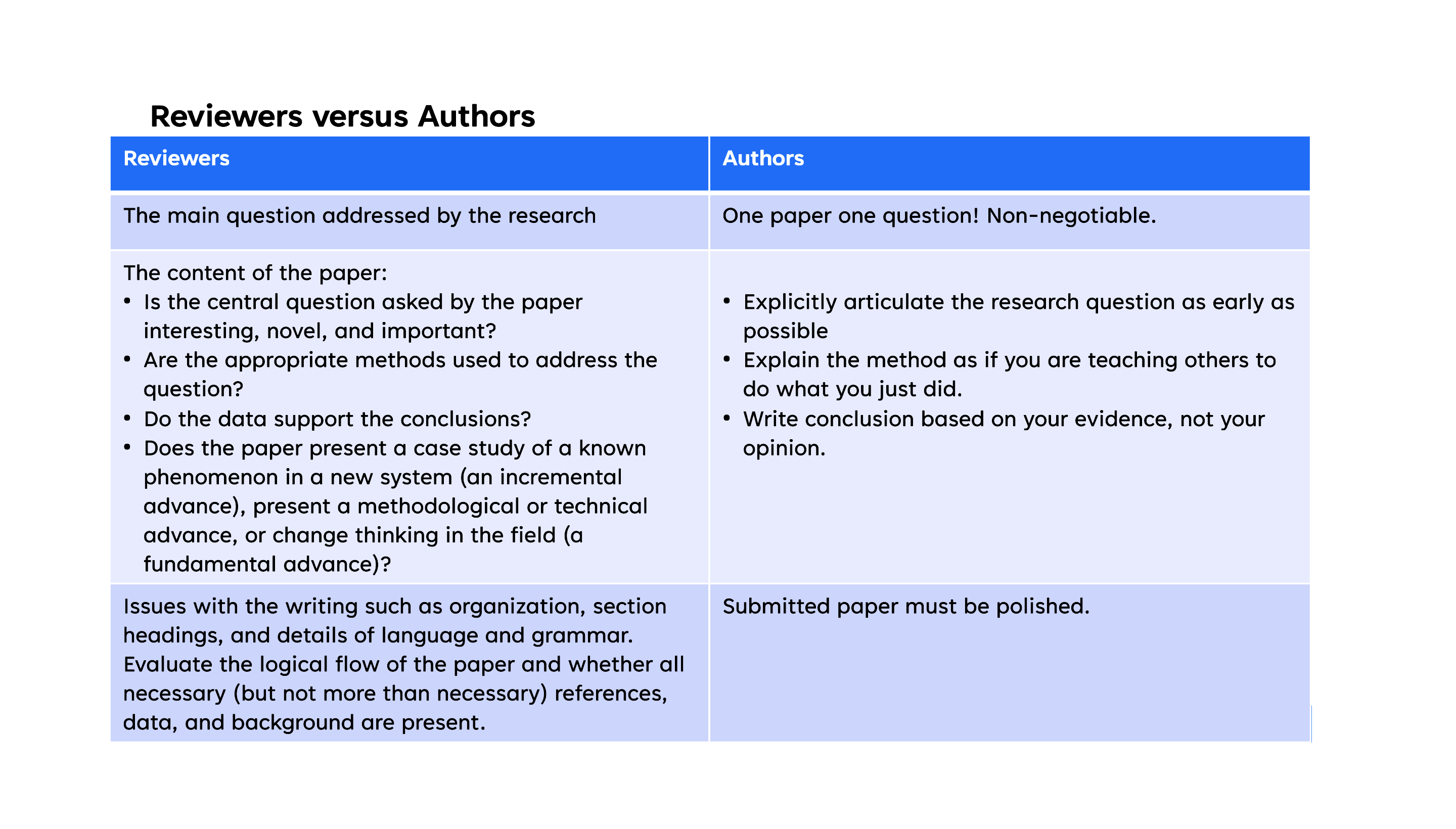

Figure 4: Key pointers to refer to when you are a reviewer vs an author. They are different sides of the same coin. Source: Jude Kurniawan. - ORCid: Your unique researcher ID. It is where your peers (including editors and reviewers) can find you and view your profile. It is automatically updated when you publish a new paper. Other information, such as the number of reviews you have done, your grants, your employment, and qualifications are also captured

- Other resources:

- Manuscript submission platforms

- SMU Libraries' publishing deals on CUP and ACM

- Author/Reviewer tutorials

- Roundtable: Publishing in Academic Journals - YouTube (I came across this just yesterday. You may jump to the 16th minute mark to learn how to be part of the pool of reviewers).

I recommend the following resource(s):